This is the second talk from the the ILTA Session – Legal Technology Innovation – Bolstering and Destroying the Legal Profession. This is from Joshua Lenon, Lawyer in Residence at Clio.

Technology is No Threat to Lawyers

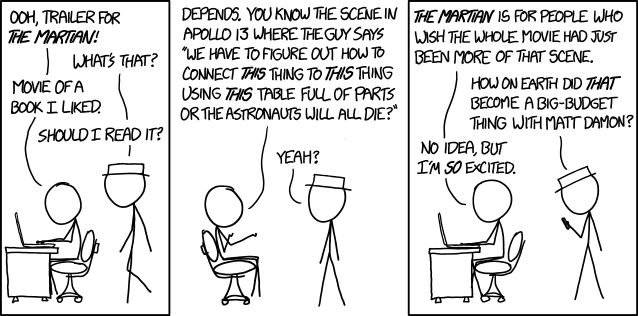

A while back, NPR’s Planet Money show issued a nifty interactive tool indicating whether or not certain employees would be replaced by technology in the future. If you looked up lawyers, you’d see the following result:

|

| (Image from NPR.org) |

The calculations that determined this statistic included such issues as:

• Do you need to come up with clever solutions?

• Are you required to personally help others?

• Does your job require negotiation?

• Does your job require you to squeeze into small spaces?

It turns out that lawyers rank high in each of these categories in favor of not being replaced by robots.

This result was pretty shocking, as most online discussion list the chances of a robot replaces lawyers as somewhere between “I, Robot” and “The Terminator.” Both movies have robots taking over, but one follows the Steve Jobs’ school of design.

Research the matter further, I delved into the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic’s (BLS) historical data on employment for providers of legal services. Did the history of technology development result in a decrease in jobs for lawyers?

When plotted from 1997 to the latest data in 2014, both paralegal and lawyers showed substantial growth in employment over that period. Lawyer employment grew 42% and paralegal employment great 111%! This represents an expansion of 320,000 jobs. Even if you only look back to 2006, the last great year of legal hiring by Big Law, you still see 10% growth in lawyer jobs since then.

Why is this growth during this time period important? It’s because it happened during one of the great expansions in human productivity in the workplace. The Bureau of Labor provides the following chart that shows the years 2000-2007 to be the second highest increase in productivity in the work place every recorded.

While the BLS did not publish productivity gains specifically for the legal service industry, other industries tracked alongside legal in the professional services category, like bookkeeping and accountants, saw productivity improvement from 2.1 to 5.0 percentage change. That’s huge, with the only greater period being the post-WWII boom that industrialized most of North America.

If lawyers and paralegals can still grow their employment levels during huge rises in productivity, that means that technology is not replacing these employees, but instead is supplementing them.

How do we know that technology is supplementing lawyers, rather than replacing them? Because the same BLS tracking data shows that other employees in the legal sector are being replaced.

Legal secretary employment has fallen from 277,000 jobs in 1997 to 212,000 in 2014. This is a 23% change, and not for the better. Legal Support Workers, Other is currently growing, but only after losing 30,000 jobs from their high in 2005.

Technology is not replacing lawyers, but is replacing the employees that support lawyers. This is akin to the change in the Industrial Revolution when plow horses were replaced with tractors. Farmers continued to exist, just now with tractors doing a lot of the hard labor for them. Lawyers continue to exist, but they are not using the tools of the past.

This change is creating large changes in the way law firms hire as well. In ALM’s 2015 report, “Law Firm Support Staff: How Many are Enough?”, 62% of law firms surveyed have decreased legal support staff levels. At the same time, 47% of firms increased their spending on staff. One conclusion is that these firms are hiring more highly trained and specialist staff.

Much like the industrial revolution decreased jobs for farriers and increased jobs for tractor engine repair specialists, law firms are now looking for support specialists in legal technology. Law firms are ditching employees that no longer fit into the new economy operating around law firms.

That’s why I think lawyers will work with robots, but will not be replaced by them.