I am more expert than most of the people in the world about The Wire, James Baldwin, Breaking Bad, David Foster Wallace, the films of Quentin Tarantino, and many, many other topics. This is not because I know much but because I know anything. The baseline used makes my claim to status meaningless. Only a minute percentage of the world’s population has any familiarity with the aforementioned. Of course I know more than people who know nothing. Being more expert than they does not mean I am an expert (I’m not).

Often, when we judge something, including ourselves, we encounter a reference class problem. Last season, was Mike Miller of the Cleveland Cavaliers a good or bad basketball player? Of the already small percentage of the basketball playing population that makes their high school squad, only .03% make it to the NBA. So Miller is, inarguably, among the basketball playing elite. At the same time, in the 52 games his coach chose to play him, Miller only averaged 2.1 points on 32.5% shooting to rank dead last in player efficiency rating among all NBA players. Miller, a 15-year veteran nearing the end of a solid career, was so unproductive that you get 816 hits on Google for “corpse of Mike Miller”. If you are putting together a pick-up basketball squad at your local rec center, probability suggests that Miller remains a phenomenal addition. If you are building an NBA rotation, you hope to have better options. Playground and NBA players are different reference classes.

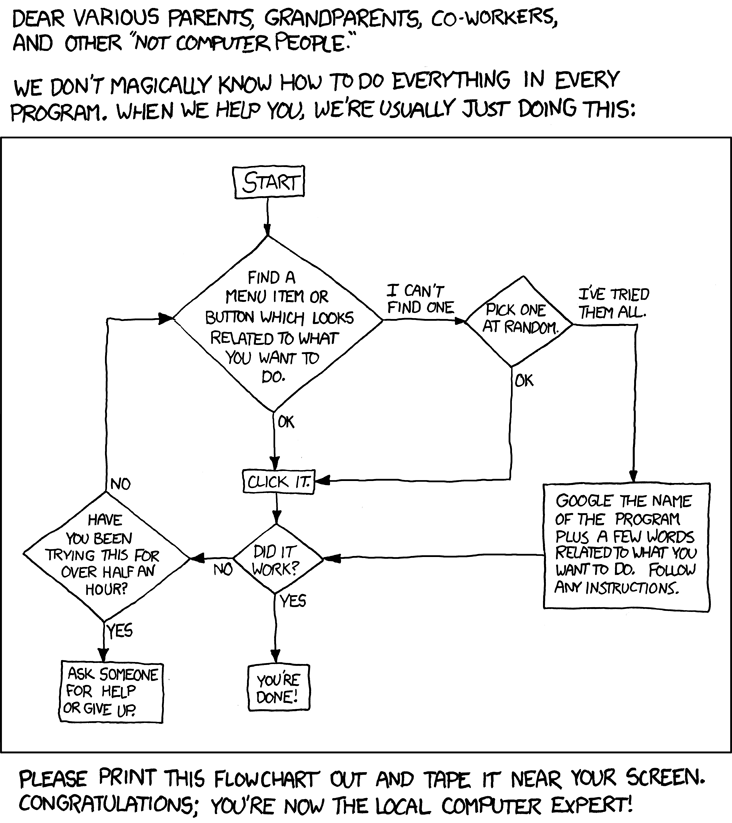

When I became a lawyer, I was immediately ordained “tech savvy” because of the reference class. My reputation was sealed when the partner in the adjacent office (an otherwise brilliant lawyer) was screaming about the computer eating valuable documents. I superheroed in to press CTRL+Z (undo). When the files resurrected, he stared at me like I was some sort of wizard. From then on, I handled ediscovery on his cases despite the inconvenient fact that, in the beginning, I knew jack all about ediscovery (that’s changed). It required dangerously little knowledge of, and facility with, technology to be tech savvy among the reference class of lawyers.

It was, of course, one thing for technophobic partners to think I knew everything about technology because I demonstrably knew more than they did. It was yet another for me to believe I was tech savvy in any meaningful sense. Yet, I started to believe just that because, well, ego. After all, I spent my days knowing more about technology than almost everyone I encountered. And those who did know more (IT professionals, word processors, and our bad-ass librarian who switched her keyboard to Dvorak) were not lawyers. The word “lawyer” was doing most of the heavy lifting in the appellation “tech-savvy lawyer.”

I had my delusions of tech adequacy punctured by a client. He happened to be in my office and asked me to turn a document into a PDF. I obliged. I printed the document, walked to the printer, walked to the scanner, and returned to my desk where he was sitting mouth agape. For months, I had been the sole associate on a PDF-intensive arbitration. He was doing the math on how much time I must have already wasted. He was apoplectic. If I had not already proven my value as a lawyer, he would have had me thrown off the case. But I had. And he didn’t. Still, he had words with the partner (the same partner who had designated me as a tech expert).

Let me be clear: I believed I was tech savvy despite the fact that I did not know how to convert a Word file into a PDF.

I was absolutely embarrassed. I changed my whole approach to technology based on the incident. But, at the time, how was I supposed to know? Everything is obvious once you know the answer. It is obvious to me now that converting one filetype (e.g., a Word document) to another filetype (a PDF) is something that the machine should do. But, to that point, no one had ever taught me that. Without training, how was I supposed to know that which I did not know?

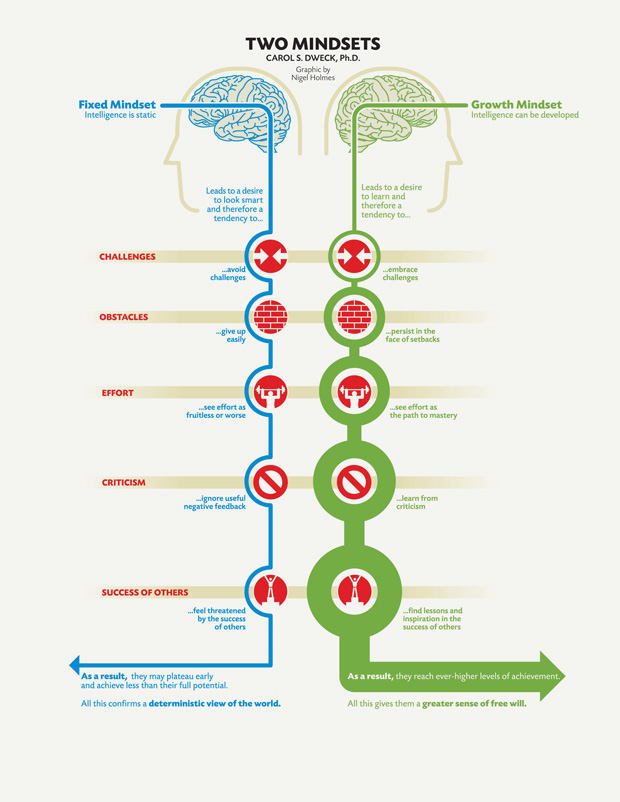

This is the problem of metacognition. In the book, Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performance from Everybody Else, Geoff Colvin explains the role metacognition plays in superior performance (h/t Farnam Street):

The best performers observe themselves closely. They are in effect able to step outside themselves, monitor what is happening in their own minds, and ask how it’s going. Researchers call this metacognition – knowledge about your own knowledge, thinking about your own thinking. Top performers do this much more systematically than others do; it’s an established part of their routine.

Metacognition is important because situations change as they play out. Apart from its role in finding opportunities for practice, it plays a valuable part in helping top performers adapt to changing conditions…[A]n excellent businessperson can pause mentally and observe his or her own mental processes as if from the outside:…Am I being hijacked by my emotions? Do I need a different strategy here? What should it be?

…Excellent performers judge themselves differently from the way other people do. They’re more specific, just as they are when they set goals and strategies. Average performers are content to tell themselves that they did great or poorly or okay. The best performers judge themselves against a standard that’s relevant for what they’re trying to achieve.

Not only do people not know what they don’t know, but their ignorance begets confidence. Metaignorance as the source of unfounded confidence is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. Illusory superiority means that the people most in need of assistance (e.g., training, education, help) are the least likely to recognize their need.

And with confidence comes ego. Many people who have declared themselves tech savvy (or some other positive designation) are only interested in that which confirms their self image. Faced with the choice of changing their self conception and proving there is no need to do so, most get busy on the proof. For lawyers, this urge towards ego preservation combines with a psychological profile that sees any admission of fallibility as an admission of incompetence.

Thus, in administering my tech competence assessment, I often come across ‘tech-savvy lawyers’ who, like I was, are merely tech savvy for a lawyer. They do well on the assessment. But they do not do perfectly. They then go to great lengths–one penned a 1,500 word memo–to explain why the features they struggled with should not be tested. While I think there is a worthwhile discussion to be had about who should be training on which skills (a later post), it amazes how people are able to delude themselves that they already know everything worth knowing. Any assessment that fails to completely confirm that self image is flawed.

When I then explain to them where the disputed features fit into a rational legal workflow, as well as the important concepts of fluency and fluidity (another later post), they, more often than not, begrudgingly concede that I may have a point. Maybe, just maybe, they might have some worthwhile things left to learn. But…there is always a but…but, they inquire, how can I expect the majority of lawyers or staff to score perfectly on a first attempt when they themselves–the cream of the crop within the profession–did not do so? I, of course, have no such expectation.

There are lawyers and staff who have flown through my assessment modules because there are people who are both legal professionals and tech savvy. But not many. For most people, there are areas where they could use training. That’s the point. Competence-based assessments are designed to identify who needs training on what, and then to verify the training has been effective. An assessment that everyone, trained and untrained, can pass on the first attempt is pointless.

Our problem is not the dearth of individuals who operate above the profession’s tech baseline. Our problem is that the baseline is so low. My goal is to raise the baseline.

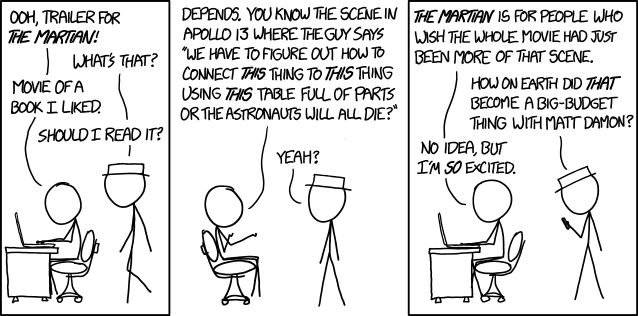

ADDENDUM: All that said, I cannot help but feel like an impostor because I am one. As I detail above, I had my bubble burst with respect to my own tech savvy. It was the epiphany I needed to start taking tech and tech training seriously. Converts make the greatest zealots. But I’ve never really recovered. Indeed, the more I learn, the more I recognize how little I know. Lawyers are no longer my reference class for properly using technology. People who are genuinely expert at using technology are my reference class (though some of them are lawyers). And they make me realize that I still have so far to go. It makes my evangelism feel hypocritical.

But this particular brand of humility is also helpful. I know enough to know how much low-hanging fruit is within our immediate grasp. But my lack of confidence in my own expertise also helps me empathize with those who are unaware of their own ignorance or who struggle with their ego. I’ve been there. Just because you have room to improve at using tech does not mean you are stupid, lazy, or bad at your job. It just means that you have room to improve at using tech, which you should do. Progress, not perfection, is the objective. And getting better is evidence of a commitment to excellence, not an indictment of past performance.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Connect with Casey on LinkedIn or follow him Twitter (@DCaseyF).