Word limits are a very good idea. Constraints benefit my regular writing (which needs all the help it can get). Here, however, I get to ramble, which has its own virtues.

As some you may have seen, Legaltech News published the first Legal Tech Assessment case study in November. This was a milestone moment for my fledgling company. But there was much more to say. So, if you are interested, what follows is an annotated version.

The case study opens:

People, some of whom are lawyers, do not like training. Training takes time out of their day. The time taken is not always offset by skills gained.

Justin Hectus knows this. As Director of Information for boutique powerhouse Keesal, Young, & Logan (KYL), he anticipated the audible rolling of eyes when he announced a basic technology training program for all associates and paraprofessionals. What he did not expect was that when the program finished every participant would answer “Yes” to the following two questions: Was it worth it? Did you learn something that you now use every day?

Lawyers will protest free food or anything else that takes them away from their desk. While a sandwich and a cookie remains the most proven method for persuading lawyers to exit their office during normal business hours, griping commences the moment it becomes mandatory. This has much to do with incessant deadlines and the attendant sense of urgency that drives lawyers. I’ve mentioned the studies on lawyer urgency in previous posts, but I think Bill Henderson captured it best in a comment:

In my experience, lawyers (and law students) are very anxious to get to work. If they feel busy, they feel productive — even if that sense of productivity is objectively wrong from a systems engineering perspective. Learning something new is non-billable time (or for students something not on the final exam). It feels wasteful to lawyers/law students because the payoff is uncertain/speculative.

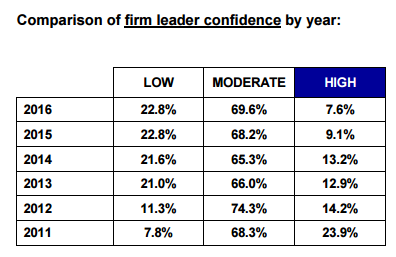

Yet, it is this same sense of urgency combined with a penchant for autonomy and alterations in the office/tech landscape that have reduced the incidence of delegation. Or, at least, that is the theory that seems to underpin many law firms’ announcements of staff reductions:

I repeatedly warn about the pernicious myth of the digital native–i.e., because they grew up with technology, younger people are automatically capable of using technology well in all its forms. The analogy I always return to is that expecting familiarity with single-purpose apps (e.g., Twitter, Instagram) to translate into facility with deep desktop software (e.g., Word, Excel) is like expecting someone who can microwave a Hot Pocket to be capable of cooking a gourmet meal. They are capable if you train them.

But disputing the conclusions re digital natives is not to dispute all of the premises. As a matter of chronology, the younger someone is, the more likely it is they grew up surrounded by and using technology. If theorizing about digital natives only went so far as to suggest a broad correlation between age and a general comfort with technology, I could get on board.

Moreover, I repeatedly lament the myth of the digital native because it is so pervasive. Almost everyone, including the digital natives themselves, seems to have bought into it. People of all ages make decisions based on the perception that the young are innately skilled with technology. This conviction could drive two different but reinforcing dynamics.

(A) Partners might see staff as less necessary based on the perception that younger attorneys don’t need them as much. So, over time, the partners alter the attorney/staff ratio. Younger attorneys therefore have no choice but to do work themselves.

(B) Younger attorneys are less inclined to delegate work to staff because of their self-perception of being good–or, at least, just as good–with technology. Staff has less to do. Observing this, the partners alter the attorney/staff ratio over time.

Those are theories. Theories are debatable. At the end of the day, there is an empirical question: are lawyers doing more labor-intensive work themselves? One of the many things that makes KYL so remarkable is that they actually endeavored to answer that question when designing their training initiative:

KYL’s recent initiative to refresh timekeeper basic technology training commenced with an empirical investigation of where it was needed most. As detailed in a previous LTN article, Hectus and his team pulled usage statistics from KYL’s document management system. Most interesting was their finding as to how the generations differed in balancing delegation and autonomy. While senior attorneys relied heavily on support staff, many younger attorneys maintained direct control over their own documents in a variety of applications.

As explained in that previous article, between 2004 to 2014, the share of Word keystrokes attributable to KYL’s senior shareholders held steady at 0%. If firm management had based their decision on their own lived experience, the training emphasis would have been entirely on staff. Fortunately, these were trial lawyers, and evidence was their primary consideration. The evidence demonstrated that, over the same time period, the share of Word keystrokes attributable to all attorneys rose from 39% to 80%.

The empirical investigation identified a subset of people, including attorneys, who might need training in specific applications. But what training? How much? While individual trainees struggle with the fact that they don’t know what they don’t know—and, therefore, do not know what questions to ask—trainers, likewise, struggle with knowing where to begin:

KYL had identified who should be proficient in which applications. But they still lacked information as to who needed training or how much. Hectus did not want to waste anyone’s time on things they already knew. He considered lecture-style info dumps an ineffective way to deliver technology training, in part, because trainees start from such different baselines. He wanted to ensure that people were learning, not just enduring a demonstration from which they took nothing. Time is a poor proxy for learning. Hectus preferred to measure learning directly.

KYL introduced the Legal Technology Assessment (LTA) to identify gaps and validate gains. The diagnostic assessment allowed users to test out of training they did not need. Some trainees tested out of training modules entirely. For those who needed training, the pre-identification of both skills and gaps reduced total training time to almost a third.

Returning to the sense of urgency, a great advantage of competence-based approaches is that once training has been made mandatory, the assessment becomes a carrot rather than a stick. Telling people you are going to give them a test creates anxiety. By contrast, telling them that you are going to permit them to test out of mandatory training is a relief.

The assessment also gives trainees something to shoot for and, as Hectus informed me, gets the competitive juices flowing (objective measurement is conducive to gamification). But, at the end of the day, it is all about the training. Proving that many lawyers and staff struggle with technology is an exercise in confirmation bias. Correcting those deficiencies in a way that translates into day-to-day improvements in quality and efficiency is the object of the exercise:

KYL does not merely claim to have enhanced legal service delivery. The firm actually has enhanced legal service delivery and can prove it. From diagnostic assessment to certification testing, KYL’s tailored training program implemented by trainer Mike Carillo improved the average LTA score more than 40 percent with substantial gains in both time and accuracy. Each participant met KYL’s competence threshold with firm personnel earning 47 portable COBOT badges (Certified Operator of Basic Office Technology) for exceptional acumen on Word, Excel, or PDF.

Most critically, the users were able to transfer what they learned to their daily practice. Associate Erin Weesner-McKinley remarks, “some tasks that I previously delegated can now be done with the click of a button, and I have a better understanding of other tasks which I still choose to delegate to nonbillable personnel or colleagues with lower billing rates.”

The idea of certifications as a means to measure and drive improvement was not new to KYL. As Hectus explained to me in an exchange (reprinted with permission) that is not part of the case study:

From the top down, the firm has committed to developing a community of experts requiring baseline competency and giving its professionals at all levels the latitude to follow their passion and become measurably “the best” in their area of choice. KYL has produced more Certified EDiscovery Specialists (through ACEDS) than any firm in the world as a % of timekeepers and KYL was the first firm in the U.S. to have certified Eclipse SE admins on staff. We have been proud contributors to the development of standards outside the firm and that has resulted in two ILTA Distinguished Peer Awards, top individual and firm honors with ACEDS, and an InfoWorld 100 designation. Our staff participated in developing our award-winning certification program in 2008 and from that point forward we have recognized that pulling out the measuring tape is one of the most important parts of continuous improvement. We support each other and take great pride in our shared accomplishments as individuals and as a firm.

It is this commitment to being a learning organization that enabled KYL to avoid the kind of staff reductions outlined above. When machines replace clerical work, clerical workers need to find new employment. Yet individuals who have been trained to work with the machine and get the most out of it are scarce. Rather than engage in a cycle of (i) waiting too long to purge staff perceived as deadweight and then (ii) scrambling to find staff with the requisite technology skills, KYL has chosen to train the talented, hard-working people already embedded in the firm’s unique culture.

I am reminded of a quote from Tyler Cowen’s Average is Over that I use often:

This imbalance in technological growth will have some surprising implications. For instance, workers more and more will come to be classified into two categories. The key questions will be: Are you good at working with intelligent machines or not? Are your skills a complement to the skills of the computer, or is the computer doing better without you? Worst of all, are you competing against the computer?

KYL is committed to making sure that its staff fit squarely in the first two categories. This requires the disciplined pursuit of better.

Measurement is central to the disciplined pursuit of better. KYL’s analysis started with measuring who spent how much time in which applications. It continued with empirical evidence that the appropriate users had increased their skill set. That evidence was then bolstered by survey data that the new skills were translating to daily work. Finally, Hectus investigated how the improvements might affect the firm’s bottom line. While it will be a while before enough post-intervention data is accumulated, Hectus was able to compare initial LTA scores to historical realization rates:

To validate this ostensible relationship between tech acumen and firm performance, Hectus compared the diagnostic test results to the firm’s realization data. Unsurprisingly, he found a correlation between high initial LTA scores and high historical realizations. More efficient service delivery appeared to translate into greater value for the firm’s clients even before the formal initiative.

My reading of this finding is that the partners were already doing a pretty good job of trimming client invoices. Although they might not have been able to identify the root cause, their gut instinct that some tasks were taking certain timekeepers too long seems validated by the data. And while the firm is dedicated to improving legal service delivery whether clients notice or not, that clients do take note is not lost on KYL:

Continuously improving client service is embedded in KYL’s DNA. But the firm is also cognizant of the way that clients are shifting the burden of proof. Beyond the merits of the LTA itself, Hectus knew that corporate law departments were already rolling out the LTA internally and asking law firms for their LTA scores. In fact, the leader of a renowned Silicon Valley law department encouraged Hectus to help KYL become the first law firm to have its support system pass the LTA. The firm did just that.

KYL recognizes that it is no longer sufficient for a firm to claim to be something—secure, efficient, innovative. Clients demand evidence. In addition to a number of traditional IT security audits, KYL has recently been through (and passed) a client review of firm-generated PDFs. The client wanted to ensure that PDFs were being properly redacted and secured. This kind of scrutiny, and the attendant marketing opportunity, suggests a greater emphasis on third-party verification.

There are some firms that, in retrospect, would have been well served to be similarly pro-active. Candidly, however, corporate law departments inserting LTA score requests into RFP’s (there was a fair amount of informal pressure) took much longer than I initially expected. I will absolutely write a post on the pace of diffusion of innovations in legal including all sorts of admissions of my own naiveté. But that is for another day. Here, I want to heap as much glory as I can on KYL.

KYL did not need to do this. The firm is what Bruce McEwan might label a “synergistic super-boutique.” I attended USC Law where the eponymous Skip Keesal is a legend. USC is not the only place. Keesal was named the most powerful person in Long Beach (the mayor was 3rd). His firm could probably get away with simply being a collection of exceptional legal minds. Yet, KYL has committed to data-driven, continuous improvement of legal service delivery that goes beyond purchasing new toys:

In 2008, KYL proclaimed “Everyone is in the IT department.” The firm recognized that information technology contributes to stellar client service. Superior lawyering remains paramount. But client communication, securing client data, and methods for generating client documents all factor into client satisfaction and retention. Much of legal service delivery—turning legal insight into concrete deliverables—now entails a technology component that combines infrastructure with user input.

At KYL, the investment in the infrastructure is ongoing. Users keep pace through the KYL Keeps You Learning framework, a program that produced the 2014 ILTA IT Professional of the Year (Hectus) and 2015 ACEDS eDiscovery Person of the Year (Janice Jaco) and utilizes the workflow-based training of the Legal Technology Core Competencies Certification Coalition (LTC4), on whose board of directors Hectus serves.

Julie Taylor, a partner in the firm’s San Francisco office, explains, “Buying the best technology is the easy part. Making sure that every member of our team knows how best to use it to the greatest effect and in a manner that is seamlessly integrated into our daily practice is the challenge. That is where we focus our efforts.”

At KYL, improvement is the way forward, not an indictment of the past. And the firm has constructed a team that is superb at driving and managing change. I know this from first-hand experience, not only from watching them run the LTA program, but also in the ways they helped us improve the LTA. Everyone could stand to get better. Everyone includes me.

My original conception of the LTA was as a single, unified assessment. One score that would indicate whether an individual possessed basic tech competence. But KYL’s empirical data on who spent how much time in which applications convinced me to break up the LTA into software specific modules (i.e., there are now stand-alone modules and micro-certifications for Word, Excel, and PDF).

Excel is a prime example. As inside counsel, I spent more time in Excel than Word. I ♥ Excel. Excel is the “most important software application of all time.” But for many lawyers Excel is an ignored green icon. Fair enough. As inside counsel, my expectation was not that every external resource be an Excel expert. My expectation was that each firm had a few identified Excel experts and a workflow designed to send spreadsheet-intensive work their way. A tool like the LTA can be used to identify and certify those internal experts. Skill validation can be as much about proper team assembly as it is about individual competence.

Further, KYL’s suggestions as to new/different content, phrasing, etc. also had an impact on the way we approached modularity. We redesigned our software so that the individual tasks became building blocks. We can now offer a menu of features and then custom build assessments based on the features selected. So as not to lose the ability to benchmark as our feature set grows, we intend to divide the micro-certifications into levels (X set of features in Level 1, Y set in Level 2). The client can then select a level for which the end user will be certified and add features from other levels to create a customized assessment. As we expand vertically (more levels) and horizontally (additional applications), we would like to get to a place where firms can construct custom, continuous micro-learning paths that culminate in competence-based assessments and micro-certifications. That vision would have been unlikely without the feedback from the KYL team.

Learning means training, not just testing. My original opinion was that many lawyers and staff already have access to training, they just don’t take advantage of it. Legal tech trainers are excellent. Training companies know their business. And the web is replete with free training content. My role, as I saw it, was to change the incentives around training, to give it some urgency. But witnessing what Carillo did with his trainees altered my conception of when and how training should be delivered. By sitting with the trainees while they took the diagnostic assessment, Carillo delivered synchronous, active learning. Though nothing can replace a live trainer like Carillo, we designed the LTA Training Edition to approximate the experience for those who don’t have immediate access to such a resource.

In short, I’m eternally grateful to KYL. They played an instrumental role in developing the LTA and in my understanding of how the LTA can fit into advancing the delivery of legal services. The amazing thing, of course, is that the LTA is only one among a host of initiatives that KYL has underway. I’m the first to admit that basic tech competence is not the be-all and end-all of legal service delivery. It is one piece of a much larger puzzle. KYL demonstrates mastery at putting those pieces together. The firm’s initiatives in knowledge management, ediscovery, information governance, and risk management are just as ambitious and just as successful. I’m honored that the LTA is counted among those successes.

_______________________________________

D. Casey Flaherty is a consultant at Procertas. He is an attorney worked as both outside and inside counsel. He is on the board of advisors of Nextlaw Labs. He is the primary author of Unless You Ask: A Guide For Law Departments To Get More From External Relationships, written and published in partnership with the ACC Legal Operations Section. Find more of his writing here. Connect with Casey on Twitter and LinkedIn. Or email casey@procertas.com.