My partners and I made a thing. We hope you enjoy it.

We poke light fun at lawyers (which all three of us are) for remaining too analogue in an increasingly digital world. Our central premise is that digital transformation is inevitable (and already happening and good and hard and we at LexFusion can help). Underpinning the premise are some hypotheses about the shape, pace, and drivers of change in legal service delivery. We might be wrong. But our bets match our predictions. We all left excellent jobs to push our chips in on an accelerating growth curve in legal innovation. In short form:

- The absolute demand for legal expertise is increasing; this will continue

- The relative cost of legal services is also increasing; this will continue until we dramatically improve productivity

- The uptick in demand powered the rise of BigLaw for decades; this peaked in 2007

- Next came in-sourcing to meet demand, somewhat keeping costs in check, largely through labor arbitrage; this has likely peaked, or will soon

- Now, to satisfy growing demand while truly bending the cost curve, we must also materially improve productivity—i.e., innovate through process and tech (the trend LexFusion is betting on)

- Innovation is necessary but hard; we need to upskill in many respects, including value storytelling

As is appropriate here, I nerd out slightly on our hypotheses below (for an even deeper treatment, let me commend to you the inimitable Jae Um, one of our advisors, from whose magnificent five-part series I borrow liberally–or check out Jae’s recent Tweet storm).

Cost 🡹 The clip hits on the general dissatisfaction with how lawyers operate in the modern age, seemingly not taking full advantage of tools that have transformed much of our world.

The world has changed; lawyers, not so much.

For $600, Amazon will next-day deliver a pocket computer (phone, camera, browser, word processor, gaming device, rolodex, clock, calendar, calculator ….) that remains constantly connected to a searchable repository of nearly all human knowledge (real and fabricated). This technology barely existed in recognizable form twenty years ago. My favorite piece of context: less than a decade after their introduction, iPhones were 120,000,000x faster than the $23,000,000 computer that weighed 600 lbs. and guided Apollo 11 to the moon. (“The iPhone is nothing more than a luxury bauble that will appeal to a few gadget freaks” – Bloomberg, 2007 😂)

Alternatively, also for $600, a junior BigLaw associate will allocate one heavily discounted hour to a client matter. Despite the apparent opportunity to be tech enabled, this associate hour is hard to distinguish from the same associate hour that cost $200 two decades ago. And because legal complexity has outpaced productivity, the number of hours required has also gone up.

Clients “feel” they get less for their legal spend dollars because they do—relative to the trajectory in electronics, logistics, consumer goods, transportation, clothing, food, etc.

Law suffers from a cost disease, previously covered here:

This is Baumol’s cost disease, an economic phenomenon that undercuts the classical theory that wages rise with productivity. The classical theory: the more productive you are, the more you are paid. The reality is that (across industries, as opposed to within them) the less productive you are, the more we need to pay you (unless there is a glut of qualified workers competing for your job). Unsurprisingly, the eponymous Baumol identified “legal services” as subject to the cost disease. And recent scholarship has concluded, “Legal services are decidedly in the stagnant sector.”

Legal productivity has increased (an argument for another day). But it has not increased relative to most other sectors of the economy. Costs have therefore risen on a relative basis. The pervasive impression that clients get less for their money comports with reality.

Critically, the impressionistic sense of ‘too many lawyers’ ‘costing too much’ is in no way limited to how law departments feel about law firms. It is also a fair description of how many enterprises feel about their own law departments.

Law is not the only sector subject to the cost disease. While law has far outpaced the Consumer Price Index, we are pikers compared to college tuition and medical care (read Bill Henderson for what this says about the A2J gap and the underconsumption of legal services among the general population).

Need 🡹

“We live in a law thick world. To secure a benefit or avoid a loss in this world, we often find that we must somehow use the law. This is as true for global corporations as it is for ordinary individuals…” Noel Semple in Legal Services Regulations at the Crossroads

Despite understandable discomfort with the growing expense of lawyers, now more than ever, clients require expert legal guidance (which, in theory, need not come in the form of lawyer-delivered services but, in practice, still largely does).

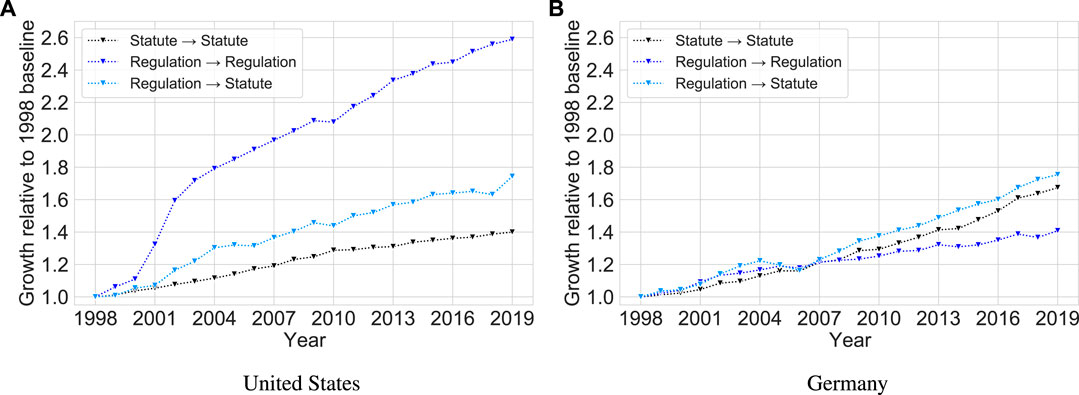

Dan Katz has labeled lawyers “complexity engineers.” Some of us create complexity. But most of us solve for complexity, helping clients navigate an increasingly complex legal landscape. Professor Katz and his collaborators have made critical contributions empirically establishing the continued growth in legal complexity (and the attendant need for legal expertise to navigate it)—see here, here, here, here. Below is the growth in statutes and regulations, as well as the growth in references thereto in corporate 10-K’s (the lawyer-influenced documents where corporations identify that which may have a material impact on their business).

Law Firm $ 🢂

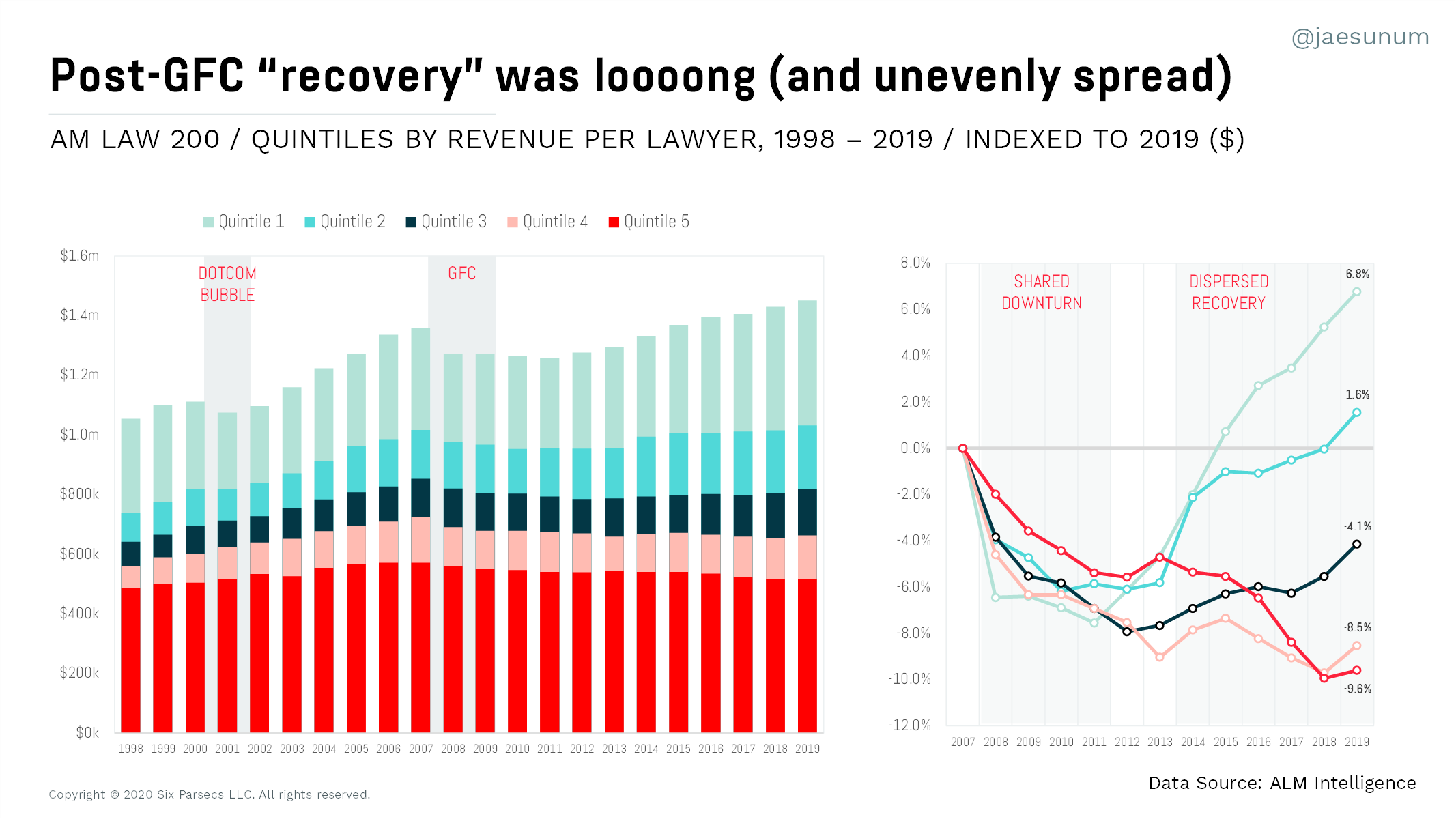

Demand outstripping supply was a winning proposition for almost every large law firm for decades. Meeting clients’ growing legal needs is propulsive force in BigLaw’s origin story. We are accustomed to charts like the one below where the growth in dollars directed to large law firms mirrors those above showing the escalation in legal complexity.

These $ charts, however, omit critical context, like measuring growth relative to GDP, inflation, and headcount. More nuanced accounting paints a different picture.

Despite prices and demand remaining on an upward trajectory in relative terms, and many positive headlines heralding banner fiscal performance in absolute terms, the pervasive sense among law firm partners that the market has tightened is also well founded (for most, not all). As an astute observer long ago explained, growth is dead.

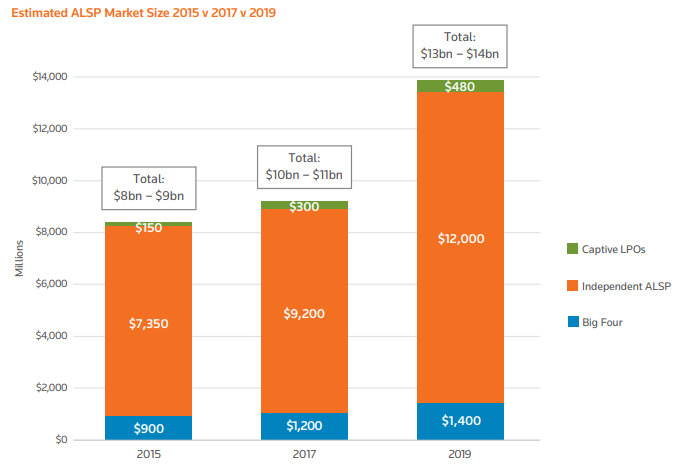

ALSPs 🡹 How is demand being met? So where is the money going? ALSPs are a key part of the story I’ve covered before (here, here) and will discuss again, just not today. Except to remind that ALSPs have a multiplier effect. Bruce MacEwen’s working hypothesis, “Simply put, for every $1.00 of revenue NewLaw gains, BigLaw loses $3.00.” And if you were to ask Bruce about this, he would tell you his working hypothesis is conservative given the data he’s subsequently interrogated. So the $15b ALSP market, adjusted for perspective, represents closer to $45b-$90b in diverted spend (cf., the AmLaw 200’s aggregate reported revenue for 2020 was $132b).

In-house 🡹 but maybe 🢂 The most game-changing realignment—in part, because it facilitated greater use of ALSPs—is the growth of in-house counsel. Since the middle of the 1990s, in-house legal departments have grown at 7.5x the rate of law firms. There are now more in-house lawyers in the United States than there are lawyers in the domestic offices of the AmLaw 200. In addition, corporations with one or more in-house counsel account for a majority of the purchase of all legal services in the United States. That is, in-house counsel have, in many respects, become the primary suppliers of corporate legal services and primary buyers of all legal services. (Note: the number of in-house lawyers has also tripled in the UK with anecdotal evidence of comparable growth around the globe – if anyone has good, recent, global numbers, please do share).

The growth of in-house counsel is multi-faceted. But a key driver is the perception (reality is more complicated) that in-house counsel are less expensive (lower salaries, no profit premium) and more effective (closer to the business, better aligned incentives).

But we’ve likely reached an inflection point—or, at least, a flattening out. According to CLOC’s 2021 State of the Industry Report, the in-house share of legal spend is already at 50%, and the cost of hiring lawyers, including in-house lawyers, continues to rise (I expect Professor Henderson to address this with additional data in the near future).

Among my operating assumptions: there is only so much work that can be insourced—for a variety of reasons, including the need for niche specialties, geographic coverage, and accordion capacity; plus, there is only so much in-house headcount corporations will stomach.

Indeed, against this backdrop of increasing demand, increasing costs, and diminishing returns to insourcing, law departments are also expected to also reduce their budgets in raw dollars. Per 2021 EY Law Survey, “88% of General Counsel reported they are planning to reduce the overall cost of the legal function over the next three years — with pressure from the CEO and board ranked as the number one reason for doing so.” On average, they expect to cut 14% (for smaller companies) to 18% (for larger companies) from their total spend.

Towards this end, according to Gartner, “by 2024, legal departments will replace 20% of generalist lawyers with nonlawyer staff. Increasingly, nonlawyers housed within the legal department provide technical and operational support. As these operational and technical roles increase, it will allow legal departments to do more with scarce resources. From 2018 to 2020, the percentage of legal departments with a legal operations manager (responsible for technical staff) grew from 34% of legal departments to 58%.”

In short, law departments are searching for ways to boost productivity while keeping headcount in check.

The Productivity Imperative and Cost Myopia. We are predisposed to think, and speak, in terms of our “runaway costs.” But the more accurate frame is our collective “productivity problem.” Cost is a symptom of the disease explained above. The rise in relative cost is rooted in legal productivity lagging behind the broader economy. Cost increases are an outcome, not a driver.

Relative cost increases combined with raw increases in demand constitute a recipe for pain. Many exogenous factors affecting demand are beyond our immediate control. The only way to meet increased demand without a consequent increase in spend is through increased productivity (which, in turn, reduces unit costs). This requires leveraging domain expertise through process and technology.

As Jason Barnwell, General Manager for Digital Transformation of Corporate, External, and Legal Affairs at Microsoft, cautions, “If capacity must increase by 10x, our current approaches break, as the option of a 10x increase in hiring is simply off the table.” Controlling costs is important. But cost myopia is counterproductive. We can’t cut our way to a 10x increase in capacity, because math. We must solve for scale.

Hence, why discount kabuki (including onerous billing guidelines) causes me angst. In the abstract, I can’t muster the energy to care that haggling is now a game we always play (procuring legal services too closely resembles buying a car). But, without even addressing the persistence of the billable hour, I can’t fathom how much energy is expended by both law departments and law firms on negotiating minute changes in the multiplier (rate) when the only sustainable path forward is collaboration on eliminating material chunks from the multiplicand (hours)—e.g., through reducing low-end friction.

The need for innovation is obvious. But is not necessarily simple, and, rarely, easy (obvious ≠ simple ≠ easy). Innovation is, therefore, often slow—like really, really, painfully slow. As in, 25 years after writing The Future of Law and 11 years after writing The End of Lawyers?, Richard Susskind is publicly proclaiming that taking the lawyers out of legal work is “harder than expected.”

This acknowledged (I’m not predicting a productivity phase shift), as I discussed here, the pandemic demonstrates how surprisingly prepared we are for digital transformation when we have no other choice, and the infrastructure is already available. Our choices are narrowing. And the inventory of shovel-ready infrastructure projects (actionable process and tech improvements) has exploded—to the point where LexFusion serving as a trusted guide to this evolving ecosystem is a viable business model (that already has imitators).

The mistaken premise of change management is that we must change (all the) minds in order to change behavior. Causation usually runs the other way. Changed behavior is often the best route to changed minds. Or, as James Clear writes, “The idea that ‘change is hard’ is one of the biggest myths about human behavior. The truth is, you change effortlessly and all the time. The primary job of the brain is to adjust your behavior based on the environment. Design a better environment. Change will happen naturally.” Fair enough. But there are always a few minds–i.e., leadership buy-in–that must be changed before the environment can be meaningfully re-designed.

The Value of Value Storytelling. Capturing mindshare is part of what makes innovation so hard and so slow. According to the 2021 EY Law Survey, “General Counsel report that increased use of technology offers the greatest opportunity for cost savings. Yet, law departments face challenges securing budget for technology and process improvement…C-suites have not been persuaded to support critical investments in legal technology and process improvement.”

Yet there is no other sustainable path. Despite this persuasion deficit, in addition to adding all the operations professionals (an imperfect proxy for process–a discussion for another day), in-house counsel still expect to triple the wallet share allocated to technology. Per Gartner, “Legal technology spending has already increased 1.5 times from 2.6% of in-house budgets in 2017 to 3.9% in 2020. Gartner predicts legal technology spending will increase to approximately 12% of in-house budgets by 2025, a threefold increase from 2020 levels.” In-house is not alone in redirecting their dollars. Legal tech is maturing and outside investment has followed suit, to the point of frothiness:

Jae’s conclusion seems undeniable, “I posit that the most valuable skill that every corporate law department needs in 2021 and beyond is the executive art of the business case.”

Improving productivity requires investment. Even then, demand may still outpace productivity gains in the near, medium, or long term. The choices could be stark: spend more or accrue operational risk (to the enterprise).

Some law departments simply need more money. Not all of them will get it (as I will discuss next post).