To summarize my thoughts:

Change is hard and intermittent. Law departments needed to graduate from simplistic insourcing to an ops-oriented mindset (relational view) and act accordingly.

If you need more than that, a long post follows. Read at your own peril.

An Overly Simplified Model of Evolution of Corporate Legal Services

Initially, the path of least resistance is to pay the premium for white-glove service. Toss it over the wall. Let the prestigious law firm deploy as many expensive bodies as they deem fit. Pay the bill.

Eventually, fiscal reality sets in. The distance between the client organization and the law firm also creates frictions. Beyond just increased costs, the challenges of communication, alignment, and our-business acumen undermine execution and outcomes.

It is often better and cheaper to bring the work in-house. Until it isn’t. Eventually, in-house departments run into all the standard diseconomies of scale while still encountering many of the peak-load issues that originally caused them to rely on outside counsel (demand for whom flattens rather than declines). That is, law departments import many of the problems of managing lawyers/matters and do not eradicate the external challenges that prompted their insourcing.

At this point (the point we’re at now), the search for substitutes begins in earnest. The growth in demand for legal services substantially outpaces the resources available to pay for them (more for less). So attempts are made to improve operations subject to constraints (run legal like a business). That means systems. Technology and outsourcing are pieces of this systems puzzle that enable a legal function to operate at scale without sacrificing quality.

Unfortunately, integration of technology and ALSPs prove not to be quick fixes (hint: there is no such thing). The law departments want it to be one way. But it’s the other way. They want it to be easy. They want it to be magic. They want technology or managed services to be similar to white-glove law firms: the client’s obligations mostly begin and end at paying the monetary cost. Once the enchanted system is in place, it is supposed to deliver superior outputs from the same inputs—i.e., no one has to materially change their behavior. The faith in immaculate, organic improvement is part of the legal profession’s “last mile problem.”

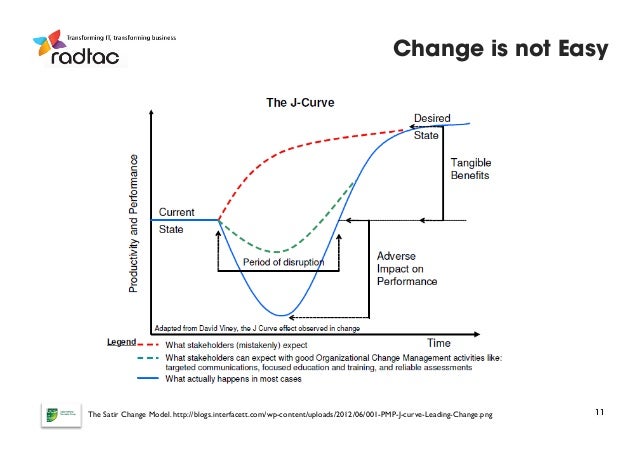

It is never that painless. On this point, I love the graph below, except for the minor problem that it is wrong.

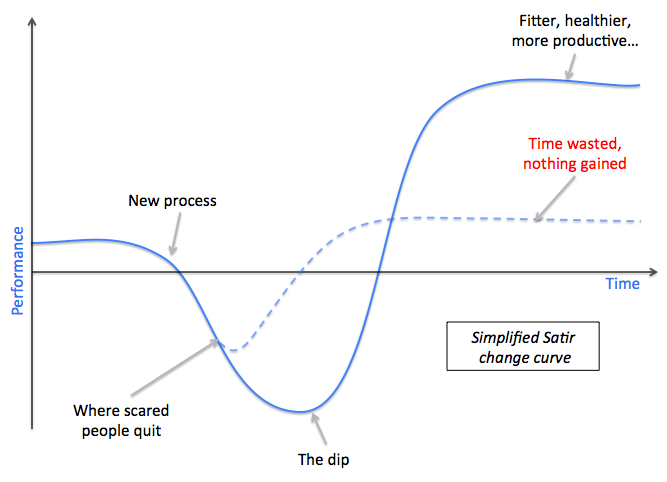

The implementation dip is real and wildly underrated. The gap between stakeholder expectations and experience is also accurate and too often ignored. But the chart goes awry by implying that all improvement projects succeed eventually. In the real world, 70% of improvement initiatives fail (and lawyers, in particular, are allergic to failure). This chart provides a dose of reality:

Except I would replace “scared people” with busy people under intense pressure to immediately deliver flawless, mission-critical work.

Systems are hard, take time, and demand constant care and feeding. Compared to systems, highly trained professionals are relatively self-starting, self-integrating, and self-regulating. Bring in a new-but-service-ready body and give them some of the load to carry. It is as close to plug-and-play as it gets

There is a compelling logic to most in-house hiring binges. But the logic only extends so far. Almost any law department with substantial external spend can demonstrate immediate ROI by bringing work in-house. But what to do when there is a hiring freeze? What to do when your department is responsible for cutting spend like every other department? One of the many dirty secrets about regularly paying exorbitant sums to external counsel is that it makes intermittent cost-cutting mandates relatively simple to satisfy. Internal headcount does not exhibit the same flexibility. And there are limits to what can be achieved, long term, by merely replacing expensive external headcount with moderately less expensive internal headcount.

Moreover—and this is important—every hire is someone who a few years down the line can join the risk-averse chorus: “But we’ve always done it this way.” Onboarding lawyers means managing lawyers. Insourcing law-firm lawyers also imports law-firm culture. Slow to change but quick to question, in-house counsel remain highly trained, autonomy-seeking issue spotters who will immediately identify the genuine pain of transitioning to a more systematic approach and then cite the inevitable implementation dip as evidence supporting their implicit position that maintaining the status quo is optimal.

One leadership failure is to succumb to the sniping and griping. But the leadership failure that most concerns me is pretending like these prognoses of pain lack merit. While the motivations to resist change may not always be righteous, the pain is real. Proceeding on the presumption that pain is avoidable is a recipe for failure.

The Pain of Managed Services

There are absolutely law departments who have successfully incorporated managed services into legal service delivery. There are also law departments who have tried and failed. What is disorienting is how similar their stories are.

The failures will generally tell you that they tried outsourcing but were displeased with the results. They put in the same kind of due diligence that would go into selecting a law firm. They sent the work to the chosen provider. What came back was unsatisfactory. They didn’t have the time or resources to train the provider to the point where the output would be acceptable. So they abandoned the initiative.

Most of the successes will tell you that they tried managed services and were initially displeased with the results. They had put in considerably more due diligence than would go into a selecting a law firm. They sent the work to the chosen provider. At first, what came back was unsatisfactory. But the department expended the time and toil to train the provider. And the provider reciprocated. Those efforts are ongoing. The initiative shows spectacular returns on investment but will never be fire-and-forget. There is constant monitoring, feedback, dialogue, experimentation, iteration…

As with most enterprise-level technology, enterprise-level managed services require a program/system administrator. I know this runs counter to most advertising pitches. I recognize everything is supposed to be self-driving these days. But I have yet to encounter a successful managed-service relationship at scale that is fly-by-wire from takeoff through landing. The people in charge of the successful relationships spend much of their time on the relationships. It is not another responsibility you just pile onto someone who is already operating at capacity.

This is not a jeremiad against managed services. I’m a strong proponent of managed services. I consider them essential to ecosystem and predict they will only grow in importance. But before embarking on a managed-services initiative, most of the future failures are living in a fantasy world about the total cost of ownership. They are focused the enormous savings potential (quite real) and ignore just how much work they are going to have to put in to realize and maintain those savings.

The Missed Opportunity (a digression)

What is true of managed services is, as I mentioned, true of technology. We believe in miracles (robot magic) to our detriment.

It is also true of law firms (and in-house teams, a topic for another day). A systems-oriented approach to outside counsel management could increase yield considerably. But it will not happen by accident. It is not automatic, let alone inevitable. It is a series of deliberate decisions full of tradeoffs followed first by the pain of implementation and then resource-intensive monitoring/management/iteration. In short, it won’t happen unless you ask and act. Even then, not every firm will prove a willing partner.

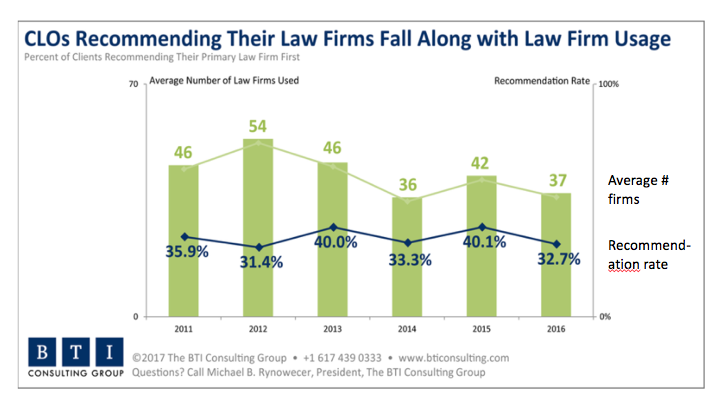

Ron Friedmann recently posted a fabulous round-up entitled Large Law Firms Must Improve Client Service Delivery. I concur with the premise, the analysis, and the conclusion. But there is something amiss with the following chart Ron cited from BTI:

Not only have clients been displeased with their law firms for years, they have been expressing this dissatisfaction in publicly available surveys. And they’ve been shedding firms. But nothing has changed. Law is a buyer’s market and has been for a decade. If the market is not changing to the buyer’s satisfaction, we have to inquire what the buyers are doing wrong. Yet what more can buyers do than voice their discontent and exit when their needs are not satisfied? Quite a bit.

Vague expressions of dissatisfaction are a poor guide to action. Even the seemingly concrete step of firing a few firms is a fairly weak signal. I promote this insane idea, captured in my writing on deep supplier relationships and strategic sourcing, that clients should have regular structured dialogue with their firms about continuously improving legal service delivery. But, per usual, the irreplaceable Ken Grady has said it infinitely better:

Clients need to get serious about understanding their supply chain and how to structure it. We hear that clients use alternative legal services providers more frequently and pull more work in-house. Those changes don’t show supply chain understanding and remodeling. They show clients swapping higher cost for lower cost in an existing supply chain.

The suppliers in the legal industry may change, but the supply change structure remains the same. A client hires a law firm. Everything is transactional, with little or no integration. Even when that client goes back to the law firm for help, each matter is transactional without integration. This is an old supply chain model. To the client’s detriment, it favors the supplier, not the buyer.

In 1980, Harvard Business School professor Michael E. Porter published the Five Factors Model. We use it to analyze an industry’s structure. We consider: 1) bargaining power of suppliers, 2) bargaining power of buyers, 3) threat of new entrants, 4) threat of substitutes, and 5) industry rivalry. Based on the analysis, we can measure the intensity of competition in an industry. Intense competition means suppliers earn lower profits.

When we look at the legal industry, the model shows low competition. Suppliers can earn outsized rewards at the expense of buyers. As competitors have entered the legal industry, the results shift a bit. But, the structure favors suppliers earning outsized rewards. This is one reason law firms can raise rates each year.

The structural shift that makes sense for the legal industry goes counter to the direction clients have taken. Jeffrey Dyer and Harbir Singh call it the “relational view”and described it in a 1998 article.

Under the relational view, suppliers and buyers integrate processes. This creates seamless, cost effective, higher quality workflows. The automotive industry is a visible example of this approach. An assembler integrates with Tier 1 suppliers, who integrate with Tier 2 suppliers, and so on. Before you say “lawyers don’t assemble cars,” I’ll point out that some clients and law firms use this same approach. The supplier and buyer work for mutual advantage rather than winner takes all.

How does this work? The supplier and buyer think long term. Working together, they set a goal. Then, they examine and integrate their existing processes. They design a value stream that flows through the entities. Value streams in the old model start and stop at each entity’s door. They build and invest in a relationship and in each other. They develop trust and expect the relationship to continue.

That relationship means the supplier will invest in innovation that benefits both it and the buyer. It means it won’t try to maximize the return on each matter. Instead, it will maximize the return on the relationship. It means the buyer will return to the supplier rather than shop every matter. The buyer invests in the supplier. Studies show that using the relational view, suppliers and buyers both do well. The supplier has a continued relationship at lower profit per transaction. But, that is better than higher profit per transaction and constant churn.

Finally, external competition keeps the parties on their toes. If a buyer stops investing, innovation will drop off. That in-house law department will be less competitive than departments in other companies. The corporation has a competitive disadvantage. If a supplier stops investing, the buyer will leave for a stronger relationship. We see that today. Buyers report they already have dropped many firms and plan to continue the trend.

Today, corporate law departments still use the transaction view for supply chain structure. They do not build competitive advantages, just temporary cost benefits. Law firms do not invest, because they have no incentives to do so. The transaction view drives low innovation, higher cost for the buyer, and higher revenue for the supplier.

Back To Managed Services

I’m going to do something ill-advised and disagree with Ken, slightly. Everything Ken wrote is gospel. If law departments treat ALSPs (or in-house teams) as lower cost substitutes for traditional law firms, they will encounter most of the same issues that engender their dissatisfaction with traditional law firms—and, likely, additional issues since the ALSPs are not designed to fill the law-firm role. My section above on failed attempts at managed services confirms that I’ve seen that movie more than once.

But I think there are material differences that favor ALSPs in the medium term. The obvious ones are that ALSP’s value proposition, culture, and corporate structure make them more cost-effective, flexible, and willing partners than most (all?) traditional law firms. In this regard, I cannot recommend enough Bill Henderson’s latest ABA Journal cover story on managed services.

I want to emphasize, however, the less obvious (but, possibly, more important) underlying shift in mindset in that law departments are more inclined (it isn’t automatic) to take the relational view with ALSPs.

Legal work is necessary. Legal work is important. Legal work is done by lawyers. The better the lawyers, the better the legal work product. Get the best lawyers you can afford. Then leave the lawyers alone to do what they do best.

This is the anti-relational view. It is not natural, but it is so ingrained that it feels natural. If it is high-end legal work, it should go to a high-end lawyer. And high-end lawyers have earned their autonomy.

The anti-relational view was great for law firms as long as everything was viewed as high-end legal work. The moat was definitional. It was high-end legal work because high-end lawyers had traditionally done it. But there is a negative pregnant: high-end lawyers don’t do low-end legal work.

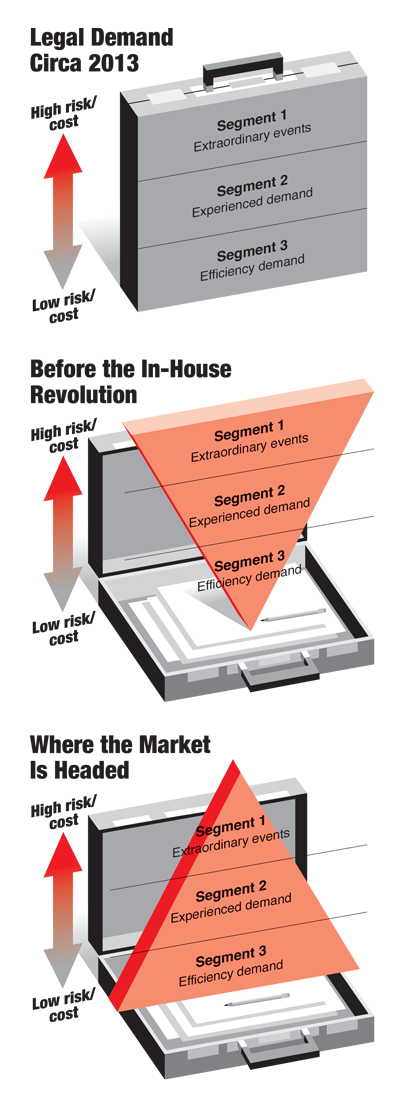

And times are changing. Law firms are not changing with it. Work is being unbundled. We are recognizing that much of ‘what lawyers do’ is necessary but low-value add. It is amenable to systematization. It is amenable to managed services and automation. I’ve enthusiastically stolen this chart from Bill’s article:

Segments 1 (extraordinary events) and 2 (experience demand) were very valuable real estate for law firms to own. That remains true. But work is increasingly being moved to Segment 3 (efficiency demand). Not all work. Law firms will not disappear anytime soon. In raw numbers, many law firms will continue to thrive. But, in percentage terms, many law firms will struggle as they are stuck in the mushy middle between the true high-end of the market and low-cost, low-margin volume players (i.e., ALSPs). We’re already seeing it.

Unbundled work is being sent to ALSPs for many reasons. But an important one is the mental categorization:

High-end, bespoke legal work to high-end lawyers with hands off (anti-relational view)

Systematized legal work to ALSPs with hands on (relational view)

Like Bill, I consider the in-house revolution instrumental to the rise of ALSPs. Size can support specialization. Specialization can breed sophistication.

In part, this means law departments have enough internal expertise to call bullsh#t. That is, they have sufficient domain expertise to identify the low-value work amenable to managed services. But that’s generally only applicable to moving work from law firms to ALSPs. What about moving work from in-house (where half of spend now resides) to ALSPs? Who calls bullsh#t on in-house counsel exclaiming that “we’ve always done it this way”?

The functional head of legal* and her legal ops lead** are the people generally charged with change management. The head of legal provides the vision and authority. Legal ops executes and maintains. Indeed, many of these managed-service relationships get moved under legal ops. Why? Because ops-oriented professionals are more likely to take the relational view. Because line lawyers who started at law firms and who were brought in-house in order to oversee law firms are predisposed to treat ALSPs just like law firms (which, to return to the digression, is one reason why the law firm relationships are so hard to change; law firms do not have a monopoly on status quo bias). Conversely, it is rare (though it does happen) for legal ops to be given sufficient dominion over existing law firm relationships. So legal ops have more of an opportunity to make an impact with ALSPs, and ALSP initiatives are more likely to be successful under legal ops. It makes sense to me that the maturation of ALSPs and legal ops are happening simultaneously.

That’s my long answer. Despite the value proposition being evident for years, ALSPs are only now reaching the inflection point because change is hard and intermittent. Law departments needed to graduate from simplistic insourcing to an ops-oriented mindset (relational view) and act accordingly.

* I use “functional head of legal” because I’ve come to appreciate that sometimes the GC/CLO is pretty far removed from the operations of the legal department. They are busy with the C-suite, board, major deals, investor relations, etc. They still provide invaluable service to the company. But they are not involved in the day-to-day operations of the department they putatively run. Instead, department leadership is delegated to one or more VP/AGC types.

**I use “legal ops lead” because titles are all over the map. I meet people who do not have the word “operations” anywhere in their title but who dedicate much, if not all, of their time to operations. Likewise, I meet people whose titles are something like “Head of Legal Operations” and quickly discover they are a glorified billing administrator. Law departments can have legal ops without a formal legal ops role. And law departments can have a legal ops role without any real legal ops.