A couple months back, I was giving a talk in a far off land (Canada) and the moderator introduced me as “the most internet famous person [he’d] ever met.” This was genteel nonsense, all the more endearing because it was absurd on its face.

He was doing obvious violence to the concept of fame. Googling “D-List Celebrity” returns an image of the prop comic Carrot Top, who has 63.4K followers on Twitter. As you can see from the panel to the right, my follower count establishes me 4% as Twitter famous as Carrot Top who himself is only 5% as Twitter famous as Emergency Kittens.

Further, the moderator’s puffery doesn’t hold up even if “fame” is being used in the local sense–i.e., widely known among the tiny subset of people who read about changes in the legal market. As the panel to the right also indicates, I am one of the least followed Geeks. There were several people in that room who are Lambert-like in their audience reach. I was not even the most famous person the moderator encountered that morning.

Rather I think what he was commenting on my ubiquity. It may be dreck, but there is no denying that my production is prolific. If you are one of those people (he is) who actively engages on the topics I cover then I am downright Kardashian in terms of saturation. Repetition has a substantial impact on perception.

In a similar vein, after a few drinks, one of my fellow presenters complimented me on my ability to “stay on message.” That was his polite way of noting that every time he sees me, which is often, I am spouting a slight variation on the same themes. But that’s the thing, I am generally not directing my talks to the people with whom I share the stage, fellow bubble dwellers who see me too often. I’m talking to an audience where 99% of the people have never heard of me and are almost completely unfamiliar with my message.

These fine gentlemen read a huge percentage of what gets written on changes in the legal landscape so they encounter me all the time. They are not alone. There is a cadre of people who are similarly engaged. But how many? My anecdotal answer: not many.

True Story 1. I used to write the legal tech column for the ACC Docket. For two years, a magazine sent to more than 35,000 inside counsel had my ugly mug opposite the coveted back inside cover. But when I would attend the ACC Annual Meeting–filled exclusively with people who get the Docket–my name/face recognition was de minimus among the people I did not already know (from the internet and other conferences). Mind you, I only got that writing gig after a fair amount of publicity elsewhere. Still, the people I met for the first time had no idea who I was, let alone anything about the ideas I espoused on the back page of the magazine they received every month.

That they did not know me was not all that surprising. Even today, I’m a niche player. But in trying to explain my interests to them, I would invariably make reference to important ACC initiatives like the Value Challenge or prominent ACC figures like Susan Hackett, Jeff Carr, and Ken Grady. Blank stares all the way around. So I would move onto ‘common’ concepts–AFAs, LPM, KM–and still elicit no spark of recognition or interest. Eventually, the conversation would turn to anodyne topics like the weather or the venue before we politely parted ways.

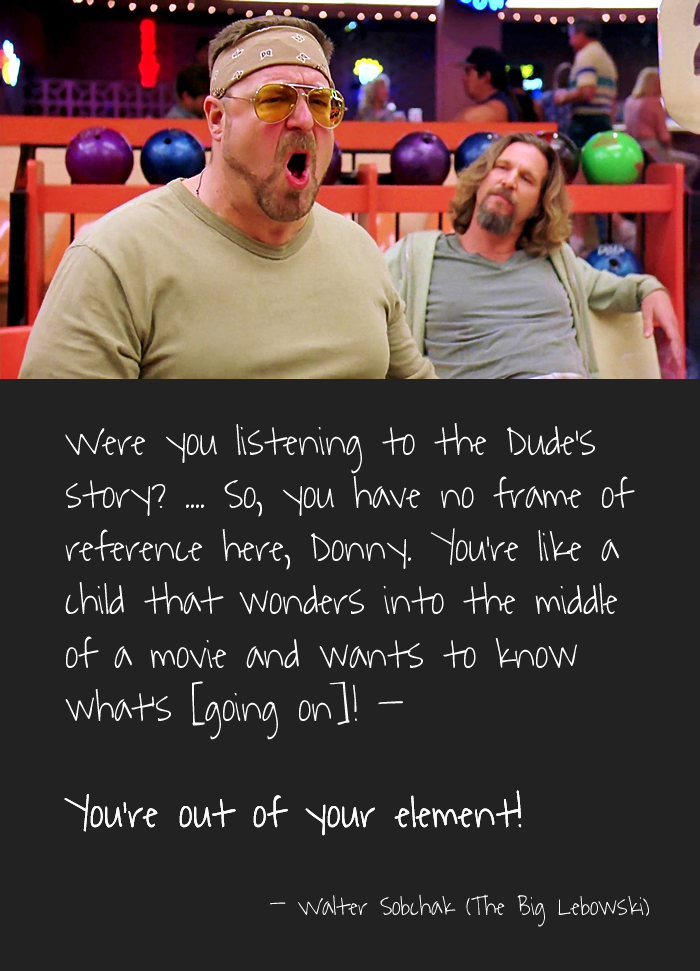

It was evident that attending the ACC Annual was the sum total of their engagement. If a topic was not covered in a panel they attended, they were not going to hear about it. And, of course, these were the self-selected individuals willing to make the extra effort to attend the ACC Annual (a great conference). The majority of their peers got their CLE’s online or for free from local law firms. I was interacting with the most active subset of in-house counsel. And most of them had no frame of reference for topics I consider fundamental to legal service delivery.

True Story 2. Last week, I was talking to a friend who was preparing an internal presentation on his firm’s successful use of alternative fees [slow clap]. He mentioned the presentation to a partner whose response was, “What’s an AFA?” That a partner at any law firm is not familiar with the term is surprising. The AFA conversation is older than I am. Such ignorance from a partner at a firm that was already broadly and successfully using AFAs is even more astounding. Except it isn’t. It is pretty easy to imagine a successful partner navigating a lucrative career without being confronted with the alternative fee concept frequently enough to internalize the abbreviation.

Most Lawyers Don’t Read, Most Clients Don’t (Seem To) Care

Imagine a conversation between an in-house counsel from Story 1 and the law firm partner in Story 2. The exchange might very well contain substantive brilliance that furthers a vital business interest. Neither story suggest that their subjects are anything other than true domain experts who render valuable client service.

But once the topic moves beyond discrete legal issues to the business aspects of the relationship, they probably struggle. Discounts would be about the long and the short of it. Regular writedowns of invoices. Annual rate-increase theater. Discounts serving as the fallback whenever the conversation veered into nebulous topics like efficiency, staffing, responsiveness, etc.

It’s not that they would fail to recognize that there were problems. It’s that they would not really know where to start with remedial action. So they would apply the discount bandaid and try to get back to their comfort zone, substantive legal issues. That is until the in-house counsel became frustrated enough to shop elsewhere, leaving the outside counsel to wonder why the phone stopped ringing.

Most lawyers don’t pay a penalty for their acute focus. When they do, it is usually not obvious, especially to them. They can still make valuable contributions to client success and be well regarded in their profession. Lack of broader interest in the process, technology, and business of law (T-shaped) rarely makes them bad lawyers. It just limits their effectiveness when more lawyering is not the optimal solution to a particular problem.

I don’t blame anyone for not reading me. Indeed, I don’t blame anyone for not reading the people I read (who are much better than me). Lawyers spend all day reading. It is natural that the little time they have off the clock is spent parenting, socializing, exercising, drinking, sleeping, or consuming popular culture. Despite some evidence to the contrary, lawyers are human.

Nor do I expect the reading habits of lawyers to change much. I expect an incremental increase in general awareness of the New Normal and an attendant increase in comfort with process and technology as necessary appurtenances to expertise in the delivery of legal services. Beyond some baseline improvements, I don’t really expect most lawyers to add much process/tech acumen on top of their domain expertise. Rather I see the continued increase and integration of legal operations, legal engineers, allied professionals, process/tech nerds, etc. The integration point is key. It’s not like these people don’t already exist. But the caste system is resilient.

I’m not exactly the first person to point to the superior returns from the division of labor supported by proper management (i.e., making people capable of joint performance). If only we had a group of people whose job required them to keep abreast of changes in the legal market and who were then empowered to modify behavior at law firms.

You’d think that “managing partner” fits that job description. On recognizing shifts in the market, you’d be right. These fine people are acutely aware of what is going on. But managing partners rarely have the unilateral authority to do that much about it because their partners are so focused on autonomy that many of them would choose it over money:

So who do the partners listen to? Clients.

A return to that topic in the next post.

ADDENDUM: At ILTAcon (amazing conference), my friends mocked me for writing so frequently and so long. Deservedly so. I can’t let go of ideas until I get them on paper. This is my scratchpad, which some of you seem to enjoy.

This was supposed to be the final installment in my series on why law firms are not doing more to change the way they deliver legal services.

In Part 1, I made the case that managing partners were well aware of the shifts in the legal landscape but were becoming more pessimistic about their firms’ ability to adapt. In Part 2, I suggested it was rational for powerful partners to resist change efforts because their success validates their approach. In Part 3, I explained the clients tend not to ask for change (voice) because they seek alternatives instead (exit). In Part 4, I cautioned that client’s signalling (exit) was too incremental to materially affect near-term behavior and therefore expressing their dissatisfaction (voice) was imperative if they want more/faster change than they are getting. Here I tried to dig a little deeper into why partners might be unaware of what they might do differently.

Because it is so important (and repetition matters), I want to conclude with some more thoughts on the role clients play. Hence one more post than originally planned.

Six posts out of a single survey question serve as Exhibit A that I write way too much.